I took a break from working on a game for several months. Work has kept me incredibly busy, as I have transitioned from a sr. engineer over to an engineer manager. I write a lot less code for work nowadays, but thankfully I will always have side projects!

Last time I talked about LOVE2D, I explained how I was managing non-git dependencies. Today, I’ll be touching on two topics: asset storage and maps.

Considering there has not been a whole lot of LOVE2D-specific content, I’ve decided to change the post-group prefix from here on out.

Assets

I’ve decided to take a really simple approach while working on this game. A lot of art is from OpenGameArt. Most of it is static, and won’t change, but in the process of hacking everything together, I’ve often cut/copied things out into new files or scaled versions of sprites.

Additionally, as much as possible, I try to track a bit of metadata about the source - license, original source page, etc - so that if anything ends up getting shipped, all artists involved can be properly credited.

This means there are a lot of “source” files - zips, etc - as well as unpacked versions, modified sprites, you name it.

At the moment, the total set of just the art assets rolls in about 100MB.

Git can totally handle this, but since this is me spending time doing

“interesting” things, I decided to look into using git-lfs.

Additionally, it allows me to have a CI pipeline for code that doesn’t need

to pull down 100MB of assets as it won’t touch them.

I definitely wanted to self-host rather than use a paid provider. Thankfully, there is a reference implementation of a git-lfs server that works well enough for now.

If I were to have multiple people working on this, I’d probably go for a paid provider - support, less maintenance, as well as not having to expose it to the internet.

I shoved the reference server in a docker container and exposed it over my VPN:

FROM golang:1.15-alpine

ENV LFS_LISTEN tcp://6983

ENV LFS_HOST 0.0.0.0:6983

ENV LFS_METADB /data/lfs.db

ENV LFS_CONTENTPATH /data/files

ENV LFS_SCHEME http

# for obvious reasons, change this

ENV LFS_ADMINUSER admin

ENV LFS_ADMINPASS admin_password

RUN apk --update add git && \

rm -rf /var/cache/apk && \

go get github.com/git-lfs/lfs-test-server && \

go install github.com/git-lfs/lfs-test-server

VOLUME /data

EXPOSE 6983

CMD $GOPATH/bin/lfs-test-server

Once this was up and running, the git repository needed a bit of configuration.

.git/config

[lfs]

url = https://internal.vpn.url

[lfs "https://internal.vpn.url"]

locksverify = false

access = basic

Finally, .gitattributes in the root of the repo needed to know what files

need to be LFS’d instead of actually committed to the repo.

*.png filter=lfs diff=lfs merge=lfs -text

*.tsx filter=lfs diff=lfs merge=lfs -text

*.pkg filter=lfs diff=lfs merge=lfs -text

src/assets/maps/* filter=lfs diff=lfs merge=lfs -text

# etc

From now on, what actually gets checked into the repo is a tiny file like this:

version https://git-lfs.github.com/spec/v1

oid sha256:long-hash

size N

Maps

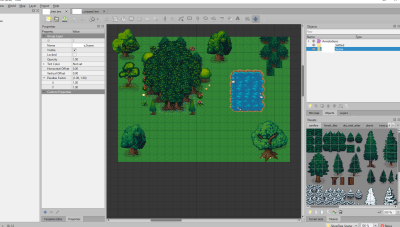

After looking into many tile-based map editors, I finally settled on Tiled. It’s a fantastic editor and incredibly easy to use. It supports exporting to a number of formats, including the one I was most interested in: lua.

There’s already a library called STI that handles the representation dumped into the lua file, which was incredibly helpful in getting something working.

Putting this together was really easy - it was just up to my imagination. One neat thing is that it has this concept of “object layers”, which I’ve used for the following:

- collision markers

- “event” triggers: teleports, area transitions, etc

- marking NPC/player spawn areas

- marking static routes that some NPCs will take

Collision detection

Collision markers were the most obvious in the beginning to me. Given that a majority of the map consists of tiled images, how would the game know that you couldn’t walk into a tree or the water? Perhaps there’s a Smart(TM) way to express that, but as a complete newcomer to designing these kinds of things, I decided to actually outline things that you can’t step on by using Tiled’s object editors and rectangles.

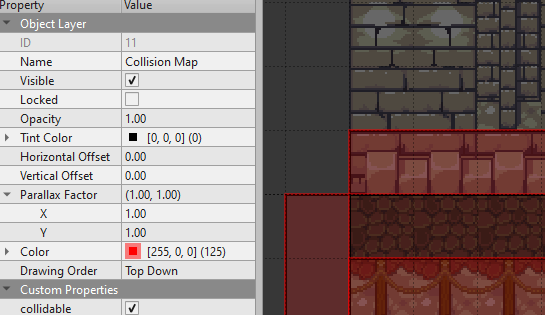

For collision detection, I used one of STI’s plugins for a library called bump.

In order for bump to know what objects are collidable, you need to add a

colldable property to each region. This is simple enough with Tiled’s object

types, which can automatically insert properties for you if you select the

type.

Anyway, as you can see from image, an entity - NPC or player - shouldn’t be able to walk off the map, into the wall, or into that nicely placed fence. Not only would that make no sense (maybe if you’re Spider-man), but because they’re a part of a layer underneath the entity, it wouldn’t look quite right. The layer with the fence would be drawn before the entity and thus would always have said entity drawn over it - not what we want. Making it impossible for that to happen is preferable in my opinion.

Side note: for the entity layer, I added a faux z-index concept by using the entity’s y-index to decide what needs to be drawn.

With bump in place, whenever an entity is moved, a call to bump:move should

occur. Bump will tell you where an entity actually ended up, given the properties

of said entity.

On entities…

While this kind of collision detection works in most cases, I have objects on the map that I don’t want to completely block off. I want the player to be able to walk up to them and be drawn in front of it or vice-versa. Vendors, lamps, and things of that sort.

Ideally these objects would be single objects, but of course they have to be drawn tile-by-tile - and suffer from the same issue of being on a different layer and thus being subject to the issue of being drawn prior to the player (or after, depending on where the entity layer is).

It seems entirely possible to add some kind of “interactable” property to each tile, but for simplicity’s sake I opted to do the following:

- copy the object in its entirety from the sheet it belongs to

- save a new image

- create an in-game entity type for “static” objects

- ahead-of-time parse the map and pluck out static objects

- generate a lua file containing definitions and position for each object

Thus these predefined entities exist in the editor, but are not rendered on-screen as-is. They’re loaded like any other entity and belong to the same layer that NPCs and the player belongs to, allowing for the faux z-index to render in the proper order given an entity’s position.

It probably isn’t the most efficient way to do things, but it works!

Note: I plan on writing a tool to create an atlas out of sprites that are handled this way so that mostly single-large images can be used as a source for any given map. Far off for now.

In order to parse the map, I found a library called go-tiled, a very

close to full-featured parser for Tiled’s .tmx files. I pass a map path

and layer name to the tool and it plucks out static_objects from said layer

and generates lua code specific to my “engine” so that it can add those as

entities in the world when it’s loaded. This also handles generating code for

NPCs and “AI paths” that are predefined.

;wq

I’m still enjoying exploring this space and learning new things along the way. Naturally, I expect that using a Real Engine(TM) would actually allow me to build a game quicker, but it has been fun to build everything from scratch. There are so many things I don’t know, and hacking, reading, watching videos from gamedevs has been incredibly eye-opening into the world that gamedevs operate in.